There seems to be a great athletic divide appearing, and there are two clear roads ahead. The first is graciously clad in lycra, and winds along a heavily filtered, motivational path. It’s lined with inspirational podcasts, self-affirming mantras, and matcha lattes, and inevitably leads to a better version of yourself. This is the Hot Girl Walk, a trend that has been cluttering local footpaths, and social feeds for the past few years, reinforcing the glossy, good-vibes-only version of aspirational femininity we’ve come to expect — and one that is increasingly indicative of a wider movement in women’s athletics.

The other path? Well, it could still involve lycra, but the hotness here is a red, contorted face, not a curated aesthetic. It’s sweat, strain, effort, and pushing past limits without any concern for how it looks. It’s a performance that momentarily forgets about being attractive — or at least the expectation of it.

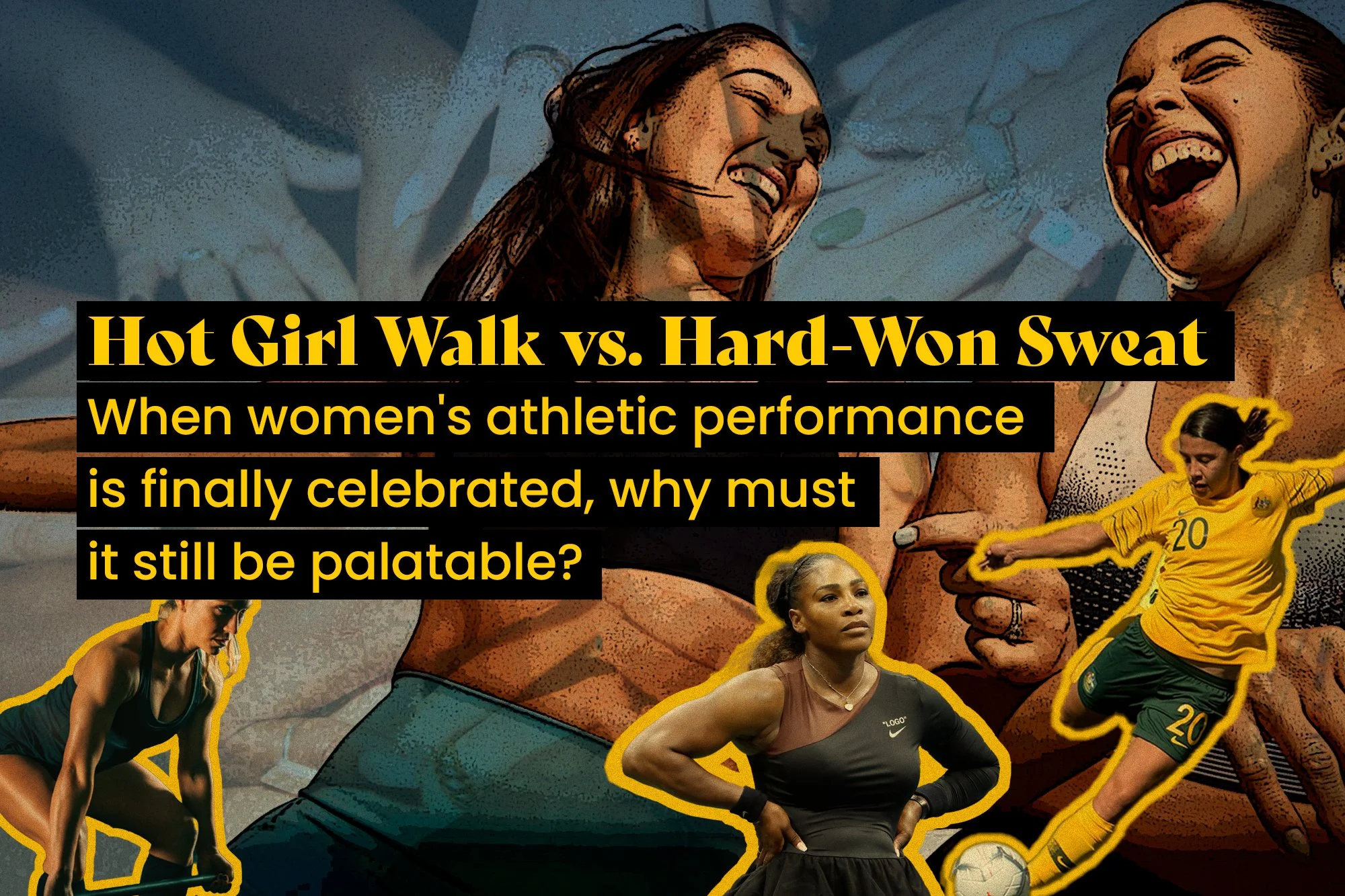

Strong, but make it sexy

The rise of female athletic performance has been significant in recent years. The 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, hosted by Australia, and New Zealand, was testament to how far women’s sport has come, drawing over two billion viewers, and generating A$1.32 billion in economic impact for Australia alone. And it’s not alone: from the dominance of Australia’s women’s swim team at the Tokyo Olympics, where for the first time male, and female participation was nearly equal, to the surging viewership of women’s rugby, basketball, and cricket, we’re seeing elite athletes who happen to be women compete at the highest levels, and deliver real cultural, and commercial returns.

And yet, in the age where women’s athletic performance is finally being celebrated, we are seeing a return to, or rebranding of, aestheticized body ideals. Where athletic performance is increasingly matched with aesthetic demands. Just look at the one-strapped sports bras desperately trying to keep things in place. But it’s not just that. Strength is welcome when it also aligns with the crafting of internalised empowerment, not just bulging biceps. And whether we like to admit it or not, all of these are marketed through the age-old adage of male fantasy, all disguised as female choice.

Male fantasy disguised as female choice is a bitter pill to swallow — and a notion that many, I’d imagine, would push against. Because why wouldn’t you? We’ve been brought up to believe we are autonomous, that our actions and choices are for us, and us alone. Not that they’re set by an unseen gatekeeper who, with a sleight of hand, reinforces what it means to be a woman through internalised rules and invisible regulations.

But this is exactly what Rosalind Gill, and Angela McRobbie have been writing and teaching about for nearly twenty years. Both well-versed and widely regarded academic theorists, they’ve written extensively on the effects of postfeminism on women’s lives. Gill argues that to be a woman is to represent ideals of choice, and autonomy. But underneath this idealisation, Gill asks: what do we sacrifice to become those things?

These ideals of choice, and autonomy play out through qualities of confidence, resilience, and a positive mental attitude. Babe…it’s not about surviving, but thriving type thing. It’s the internalised belief that we, as women, are fully responsible for our own happiness, and that the outside world, or any systemic barriers, have little to do with it.

This masks the darker workings and persistent pressures of what it means to “be a woman,” and the ever-narrowing boundaries of acceptable femininity. Because as standard, we are supposed to look hot…to attract. But alongside this relentless need to upgrade externally (the glow-up: hair, makeup, nails), there’s now a growing pressure to upgrade internally too: to manage feelings, to optimise mood.

This was summed up, almost too perfectly, by the berated and celebrated Australian influencer Chris Griffin, who stated that a man with a busy life needs:

“Calm, harmony, peace and love… This is why I heavily encourage hot girl walks. I would love my partner to go on a hot girl walk with her friends every day. She gets this feminine energy, they get to talk their shit and they get to have a bit of excitement about their day.”

Whether you agree with Griffin or not, he captured the underlying logic of the Hot Girl Walk, and its purpose. These kinds of walks keep women tethered to the fashion and beauty industries, expected to look hot even while exercising, while also maintaining a form of internal self-surveillance that ensures we remain more palatable to the rest of the world.

The post-feminist masquerade

Angela McRobbie calls this cultural contradiction the “postfeminist masquerade”. The idea that women today must appear confident, independent, and ambitious, while still performing a kind of hyper-femininity that keeps them desirable, emotionally contained, and compliant. It’s the everyday mask most women put on just to get through the day. Not necessarily to please, but to make things a little less hard.

This is a cultural shift that’s slippery by design. Women are no longer told to stay home, be modest, and raise the kids. They’re encouraged to be ambitious, to succeed (While often still doing all those things.) But now they’re also expected to do it all with glowing skin and an equally glowing selfhood. Yes, that old chestnut — the “woman can have it all” rhetoric.

So how does this work? Where femininity was once tethered to marriage, men, and the home — i.e. domestication — it’s now migrated to commercial culture. Today, beauty routines, wellness trends, fitness hacks, and self-optimisation rituals quietly police what it means to be the “right” kind of woman. Femininity has become a full-time performance. A project with shifting rules, but one fixed outcome: acceptance.

But why the shift at all?

Here lies the darker crux. Women are no longer economically dependent on men. They have careers. And frankly, most households couldn’t survive on one income if they tried. That reality has destabilised traditional gender roles. In response, the pressure to be hot, calm, and emotionally compliant looks like a counterbalance — a soft, aesthetic way to restabilise a system that’s been shaken.

Hot Girl Walks aren’t just about wellness. They’re about reminding women what kind of femininity still gets rewarded in public.

Because the storylines and imagery that proliferate the most are still of hot, happy, attractive women doing something sporty — but only attractively. Not the women who are reshaping the very foundations of sport, who grunt, sweat, and threaten to change its power structures. And I think that tells us everything about where we still are — and if we’re not careful, where we’re heading.

How brands repackage power in pink

Even as elite women’s sport gains cultural legitimacy, so many brands and franchises still lean into the aesthetic and emotional management of women when it comes to athletic performance. The persistent framing of the female athletic body through a lens of aesthetic discipline, self-surveillance, and hyper-femininity hasn’t gone away — it’s simply evolved and is more sneaky with its message.

Nike, one of the great founding sports brands, celebrates the everyday athlete as much as it does their pros (until they become pregnant, of course).

But case in point is the “Feel Your All” 2022 campaign that shifted from effort and mindset to the emotional empowerment of women specifically. A campaign featuring female athletes framed in soft lighting, smooth camera movements, and an introspective mood. Every angle of their bodies is beautifully choreographed, and there’s even the exciting validation of having perfectly painted nails. This is in stark contrast to “You Can’t Stop Us,” which did feature women but predominantly men and focused on dominance, grit, and collective power — not collective giggles.

Then there’s Lululemon, which is built on a wellness narrative for men, and women that presents them differently, albeit subtly. The men’s campaign “Strength to be” focused on the internalised mental strength of men; it still used words “charge,” and “strength,” and also led with traditionally aggressive sports such as boxing. Dark, and bold colours accompanied men staring into the camera, they are read as in control.

Conversely the women’s “Embrace” campaign that focuses on connecting with women on an emotional level by highlighting the feeling of comfort, support, and confidence. Within the spot we see women’s passive, long lingering camera movements explore their body; it is not threatening, not competitive — rather soft, poised, and introspective in stillness.

Then beyond brands, there is the gendered coverage of female, and male athletes. Ash Barty, who was praised for being “humble” and “gracious,” less often for her killer backhand, or dominance. Contrast that with someone like Nick Kyrgios. Known for his outbursts, and unpredictability, Kyrgios is regularly called fiery, or rebellious — but rarely asked to be more palatable. No one’s suggesting he tone it down, or smile more. His athleticism is taken as a given, even when his behaviour is divisive.

Then there’s Serena Williams, who has faced so much body criticism. Continued questioning around her “muscular” build is not only an attempt to drown out her physical abilities, and focus on her lack of femininity, but an intersectional example of the pressures Black women face — that their strength is seen as a threat rather than aspiration. Yet, strong black male athletes such as LeBron James, or Usain Bolt are celebrated for their physical power, charisma, and showmanship. Their strength is seen as heroic, not threatening.

Or what about Triple M host, Marty Sheargold, little outburst over the Matildas, where he stated:

“You know what they remind me of? Year 10 girls. All the infighting and all the friendship issues, ‘The coach hates me, and I hate bloody training and Michelle’s being a bitch.”

Yes, it led to him stepping back from his role, but at no point did anyone in that studio challenge him, showing just how culturally permissible it still is to infantilise women, and reduce team dynamics to petty drama. Female athletes are still held accountable for being palatable and feminine.

Moving beyond looks to legacy

So, what now? Long gone are the traditional beauty ads, and the supermodel era of the ’90s, and 2000s. The sporting arena is now the latest site where brand-led post-feminism reshapes female acceptability — through style, sex appeal, and self-discipline. It’s become the new teaching ground for women, quietly instructing us on who we’re supposed to be.

In doing so, brands, and media aren’t just undermining the very consumers they claim to champion (or the progress they say they support) — they’re also overlooking the deeper cultural, and commercial impact of real performance

As recent sporting events have shown, women’s value lies far beyond their body aesthetic. It’s not how she looks doing it. It’s that she’s doing it.

Because if we keep mistaking aesthetic performance for actual progress, we risk losing sight of the real win: not just being seen, but being seen on our own terms.